The psychology of color as it relates to persuasion is one of the most interesting–and most controversial–aspects of marketing.

The reason: Most of today’s conversations on colours and persuasion consist of hunches, anecdotal evidence and advertisers blowing smoke about “colours and the mind.”

To alleviate this trend and give proper treatment to a truly fascinating element of human behavior, today we’re going to cover a selection of the most reliable research on colour theory and persuasion.

Misconceptions around the Psychology of Colour

Why does colour psychology invoke so much conversation … but is backed with so little factual data?

As research shows, it’s likely because elements such as personal preference, experiences, upbringing, cultural differences, context, etc., often muddy the effect individual colours have on us. So the idea that colours such as yellow or purple are able to invoke some sort of hyper-specific emotion is about as accurate as your standard Tarot card reading.

The conversation is only worsened by incredibly vapid visuals that sum up colour psychology with awesome “facts” such as this one:

Don’t fret, though. Now it’s time to take a look at some research-backed insights on how colour plays a role in persuasion.

The Importance of Colours in Branding

First, let’s address branding, which is one of the most important issues relating to color perception and the area where many articles on this subject run into problems.

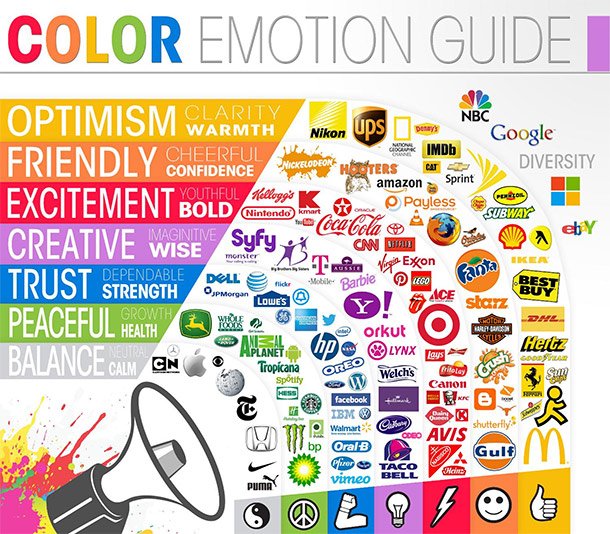

There have been numerous attempts to classify consumer responses to different individual colours:

… but the truth of the matter is that colour is too dependent on personal experiences to be universally translated to specific feelings.

But there are broader messaging patterns to be found in colour perceptions. For instance, colours play a fairly substantial role in purchases and branding.

In an appropriately titled study called Impact of Color in Marketing, researchers found that up to 90% of snap judgments made about products can be based on colour alone (depending on the product).

And in regards to the role that color plays in branding, results from studies such as The Interactive Effects of Colors show that the relationship between brands and color hinges on the perceived appropriateness of the color being used for the particular brand (in other words, does the color “fit” what is being sold).

The study Exciting Red and Competent Blue also confirms that purchasing intent is greatly affected by colours due to the impact they have on how a brand is perceived. This means that colours influence how consumers view the “personality” of the brand in question (after all, who would want to buy a Harley Davidson motorcycle if they didn’t get the feeling that Harleys were rugged and cool?).

Additional studies have revealed that our brains prefer recognizable brands, which makes colour incredibly important when creating a brand identity. It has even been suggested in Color Research & Application that it is of paramount importance for new brands to specifically target logo colours that ensure differentiation from entrenched competitors (if the competition all uses blue, you’ll stand out by using purple).

When it comes to picking the “right” colour, research has found that predicting consumer reaction to colour appropriateness in relation to the product is far more important than the individual colour itself. So, if Harley owners buy the product in order to feel rugged, you could assume that the pink + glitter edition wouldn’t sell all that well.

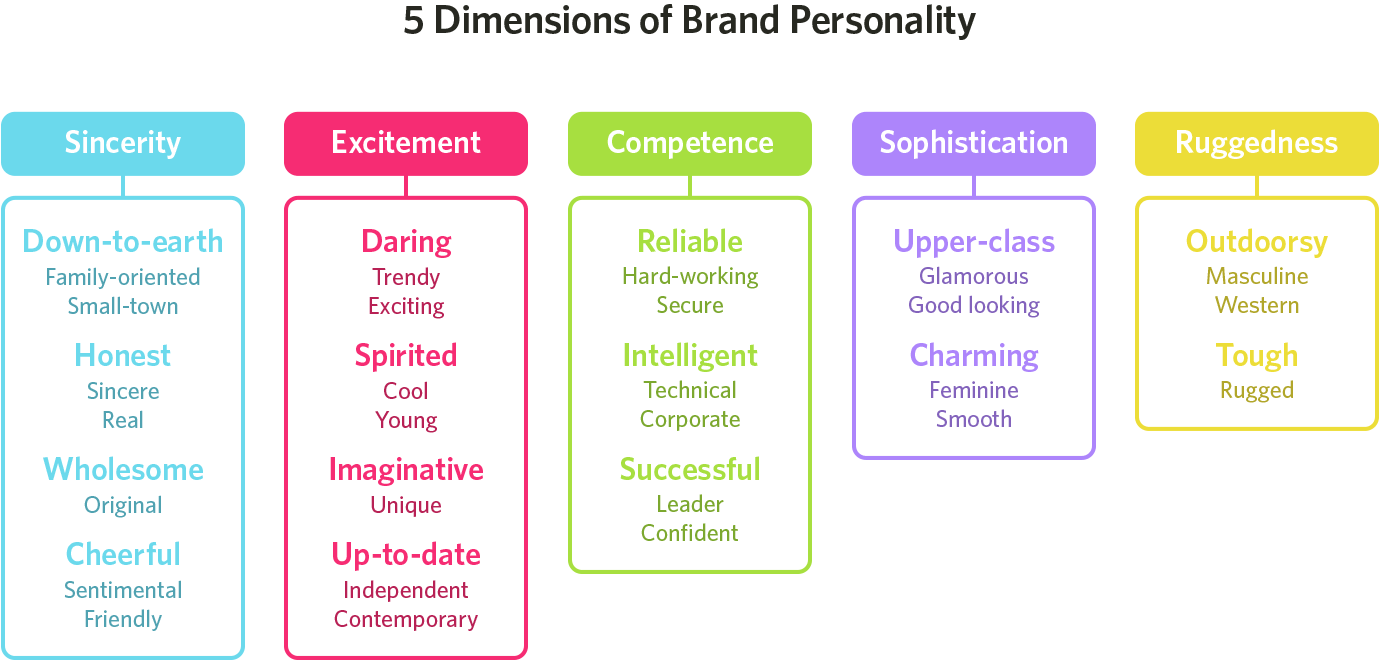

Psychologist and Stanford professor Jennifer Aaker has conducted studies on this very topic via research on Dimensions of Brand Personality, and her studies have found five core dimensions that play a role in a brand’s personality:

.

Brands can sometimes cross between two traits, but they are mostly dominated by one. While certain colours do broadly align with specific traits (e.g., brown with ruggedness, purple with sophistication, and red with excitement), nearly every academic study on colours and branding will tell you that it’s far more important for colours to support the personality you want to portray instead of trying to align with stereotypical colour associations.

Consider the inaccuracy of making broad statements such as “green means calm.” The context is absent: sometimes green is used to brand environmental issues, like Seventh Generation, but other times it’s meant to brand financial spaces, such as Mint.

And while brown may be useful for a rugged appeal — see how it’s used by Saddleback Leather — when positioned in another context, brown can be used to create a warm, inviting feeling (Thanksgiving) or to stir your appetite (every chocolate commercial you’ve ever seen).

Bottom line: There are no clear-cut guidelines for choosing your brand’s colours. “It depends” is a frustrating answer, but it’s the truth. However, the context you’re working within is an essential consideration. It’s the feeling, mood, and image that your brand or product creates that matters.

Color trends for men and women

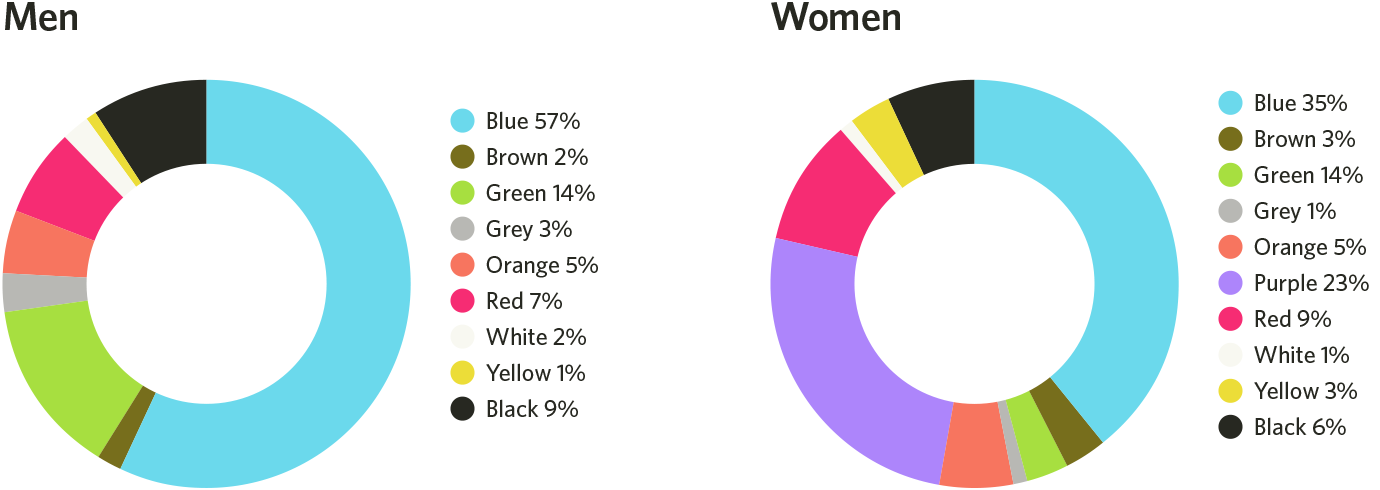

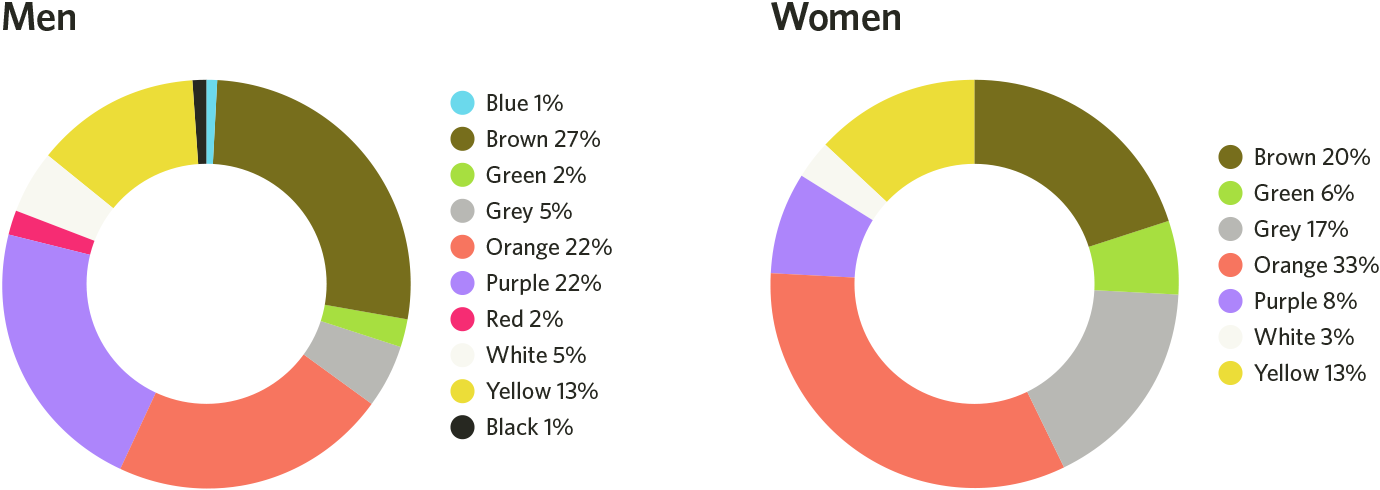

One of the more interesting examinations of this topic is Joe Hallock’s work on “Colour Assignment.” Hallock’s data showcases some clear preferences in certain colours across gender (most of his respondents were from Western societies). The most notable points in his images are the supremacy of blue across both genders and the disparity between groups on purple.

It’s important to note that one’s environment—and especially cultural perception—plays a strong role in dictating colour appropriateness for gender, which in turn can influence individual choices. Consider, for instance, this coverage by Smithsonian magazine, detailing how blue and pink became associated with boys and girls respectively, and how it used to be the reverse.

Here were Hallock’s findings:

Men’s and women’s favorite colors

Men’s and women’s least favorite colors

Additional research in studies on color perception and color preferences show that when it comes to shades, tints, and hues, men generally prefer bold colors while women prefer softer colours. Also, men were more likely to select shades of colours as their favorites (colours with black added), whereas women are more receptive to tints of colours (colours with white added).

Although this is a hotly debated issue in color theory, I’ve never understood why. Brands can easily work outside of gender stereotypes — in fact, I’d argue many have been rewarded for doing because they break expectations. “Perceived appropriateness” shouldn’t be so rigid as to assume a brand or product can’t succeed because the colors don’t match surveyed tastes.

Colour coordination and conversions

The psychological principle known as the Isolation Effect states that an item that “stands out like a sore thumb” is more likely to be remembered. Research clearly shows that participants are able to recognize and recall an item far better — be it text or an image — when it blatantly sticks out from its surroundings.

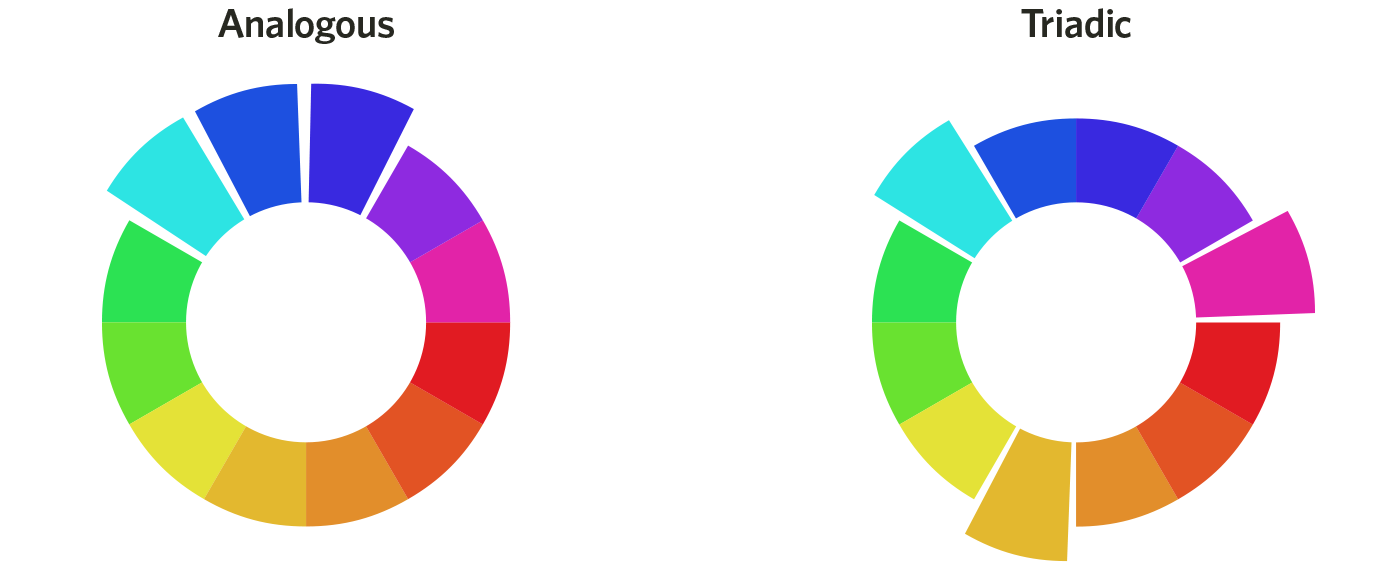

Two studies on color combinations, one measuring aesthetic response and the other looking at consumer preferences, also find that while a large majority of consumers prefer colour patterns with similar hues, they favor palettes with a highly contrasting accent colour.

In terms of colour coordination, this means creating a visual structure consisting of base analogous colors and contrasting them with accent complementary (or tertiary) colours:

Another way to think of this is to utilize background, base, and accent colours, as designer Josh Byers showcases below, to create a hierarchy on your site that “coaches” customers on which color encourages action.

Credit: Josh Byers

Credit: Josh ByersWhy does this matter? Although you may start to feel like an interior decorator after reading this section, understanding these principles will help keep you from drinking the conversion rate optimization Kool-Aid that misleads so many people.

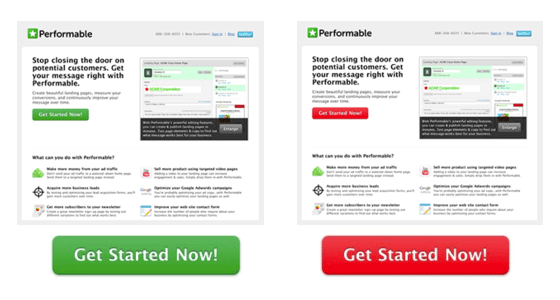

Consider, for instance, this oft-cited example of a boost in conversions due to a change in button colour.

Credit: Joshua Porter

Credit: Joshua PorterThe button change to red boosted conversions by 21 percent. However, we can’t make hasty assumptions about “the power of red” in isolation. It’s obvious that the rest of the page is geared toward a green palette, which means a green call to action simply blends in with the surroundings. Red, meanwhile, provides a stark visual contrast, and is a complementary colour to green.

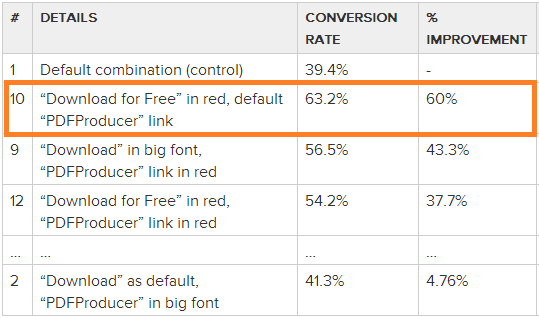

We find additional evidence of the isolation effect in multivariate tests, including one conducted by Paras Chopra published in Smashing Magazine. Chopra was testing to see how he could get more downloads for his PDFProducer program, and included the following variations in his test:

Can you guess which combination performed the best? Here were the results:

Example #10 outperformed the others by a large margin. It’s probably not a coincidence that it creates the most contrast out of all of the examples. You’ll notice that the PDF Producer text is small and light gray in color, but the action text (“Download for Free”) is large and red, creating the contrast needed for high conversions.

A final but critical consideration is how we define “success” for such tests. More sign-ups or more clicks is just a single measurement; often a misleading one that marketers try to game simply because it can be so easily measured.

Why we prefer “sky blue” over “light blue”

Although different colors can be perceived in different ways, the descriptive names of those colours matters as well.

According to a study titled “A rose by any other name…,” when subjects were asked to evaluate products with different colour names, such as makeup, fancy names were preferred far more often. For example, “mocha” was found to be significantly more likeable than “brown,” despite the fact that the subjects were shown the same colour.

Additional research finds the same effect applies to a wide variety of products; consumers rated elaborately named paint colours as more pleasing to the eye than their simply named counterparts. It has also been shown that more unusual and unique colour names are preferable for everything from jelly beans to sweatshirts. For instance, crayon colours with names such as “razzmatazz” were more likely to be chosen than names such as “lemon yellow.”

Finding your own palette

We’re at the end of this post and there’s still no cheat sheet for choosing the perfect colour in sight. In fact, we may have raised more questions than answers!

Truth is, the kaleidoscopic nature of colour theory means we may never have definitive answers.

However, just because a topic is peppered with plenty of “maybes” and “sort ofs” doesn’t mean we should stop thinking critically about it. Use the research available to challenge preconceived notions and to raise better questions; it’s the one consistent way to reach better answers.

As strange as it may seem, choosing creative, descriptive and memorable names to describe certain colours (such as “sky blue” over “light blue”) can be an important part of making sure the colour of the product achieves its biggest impact.